Email: support@vespaagogo.com

Email: support@vespaagogo.comCultural Insights

- Home

- Travel Tips

The Living Altar: A Traveler's Guide to Ancestor Worship in Vietnam

2025-09-01

To truly understand Vietnam, look past the towering skyscrapers and bustling avenues. Find a quiet moment and look at what lies at the spiritual heart of every family: the home altar. This isn't just decoration; it's a living symbol of an invisible family tree, with roots deep in the past and branches reaching toward the future. This is the world of Vietnamese Ancestor Worship, a tradition of the heart that shows you a deeper, warmer Vietnam.

A Closer Look at the Altar

Your first encounter will likely be visual. You’ll see these ornate altars in homes, shops, and even offices. Look closer, and you'll notice the details. You might wonder what fills the incense burner - often it's sand for convenience, but traditionally, it’s a bed of uncooked rice. For a country built on a wet-rice civilization, rice symbolizes life and prosperity.

The offerings are a feast for the eyes. You’ll see fresh fruit, small cups of tea, and vibrant flowers. While many flowers are used, you will often see bright yellow chrysanthemums. This is no random choice. Symbolically, yellow represents respect and nobility. Practically, these hardy flowers have been an affordable and beautiful offering for generations.

An Offering of Love and Memory

Lighting incense is a central act of worship. As a guest, it's an honor to be invited to participate, so always wait for your host to ask you first.

The number three symbolizes the trio of Heaven, Earth, and People

If invited, you will likely be given one or three sticks. This is because odd numbers are considered positive, with the number three being especially meaningful as it represents Heaven, Earth, and People. Simply hold the incense with both hands, bow your head in quiet respect, and place it in the burner. The gesture itself is a beautiful act of understanding.

The most important offering is food, usually the favorite meals of the person who has passed. This leads to a common question: what happens to the food afterward? It’s happily eaten by the family! This is called “thụ lộc” which means “to receive the blessings.” The family believes the ancestors enjoy the spiritual essence of the food, leaving the physical meal, now blessed, for their descendants to share.

Have you ever seen a scene like the one in this picture while walking through Vietnam and wondered what it’s all about?

This fascinating practice is the burning of paper offerings (known as vàng mã). It's based on a folk belief that by burning these paper items - replicas of money, clothes, or even luxury cars - you are “sending” them to your ancestors. It’s a unique act of care to ensure beloved family members have all the material comforts they might need in the afterlife.

"Remember the Source": The Heart of the Tradition

So, why all this care? It all comes back to a core Vietnamese value: "Uống nước nhớ nguồn" which means, "When you drink water, remember the source." This isn't about worshipping a distant god, it's about staying connected to your family roots.

When you visit a Vietnamese home, don't be surprised if you see photos of several different people proudly displayed on the family altar. So, who exactly are these honored individuals?

They are the family's direct ancestors. Typically, a family will worship the most recent three to five generations. This tradition keeps the connection deeply personal, as it focuses on grandparents and great-grandparents who are still held in living memory. They are not seen as distant figures, but as beloved guardians who continue to watch over and protect the family.

Ancestor worship here is a collective act, honoring many family members at once

A Widening Circle of Care

This respect for roots expands outward from the home in fascinating ways:

- In the family: The home altar is the foundation.

- In the village: In the countryside, community temples honor a Thành hoàng làng, or a "guardian spirit" of the village.

- In the community: This spirit of care extends even to the forgotten. You may see offerings placed outside homes, especially in the 7th lunar month. This is cúng cô hồn, an offering for "wandering souls" who have no family to care for them. It’s an act of compassion to ensure no spirit is left lonely.

- In the nation: The circle is completed at the national level with the worship of the Hùng Kings, the legendary founders of Vietnam. Their commemoration day is a national holiday, uniting all Vietnamese people.

Hùng Kings' Commemoration Day is the most important national holiday in Vietnam

The Great Gatherings: When Families Honor Their Roots

While honoring ancestors is a daily custom, the tradition truly comes alive during two major family events: the death anniversary and the Lunar New Year (Tết).

The most unique is the death anniversary (Đám Giỗ). Forget the idea of a somber funeral, this is a joyful celebration of life. On this day, families cook a large feast featuring the favorite dishes of the person who passed away. After a simple offering on the altar, everyone gathers to share the meal, turning the occasion into a warm and bustling family reunion.

A 'Giỗ' isn't a somber occasion, but a vibrant family get-together filled with a cheerful and bustling atmosphere

The second great occasion is Tết, the Vietnamese Lunar New Year. This is the biggest holiday of the year, and ancestors are considered essential guests. Before the new year arrives, families perform a special cleaning ritual for the altar. This includes clearing out the old incense stems from the past year, leaving just a few behind to ensure that the ancestors' blessings continue seamlessly into the new year.

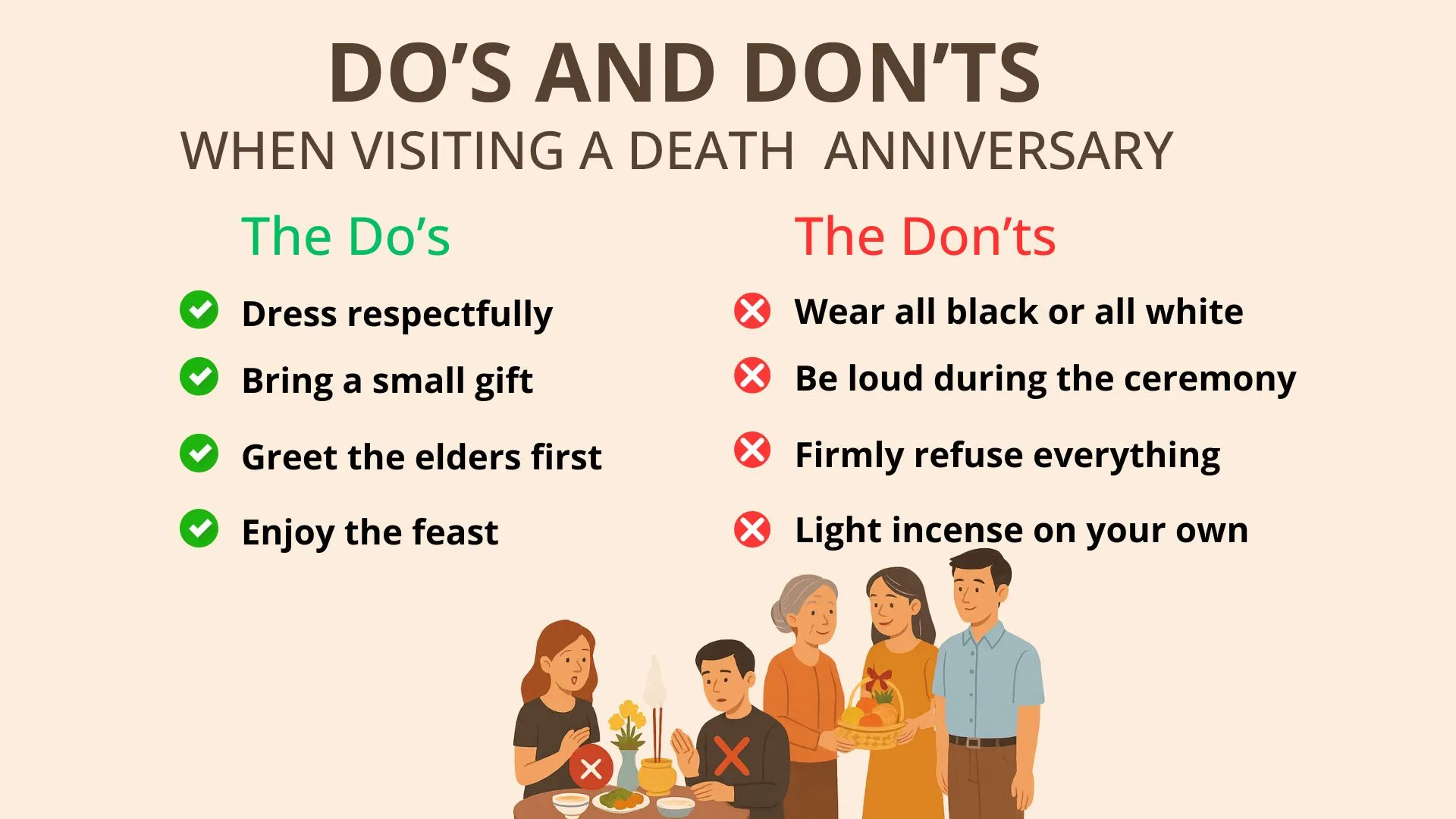

A Practical Guide for Guests at a Death Anniversary

If you're a traveler in Vietnam and you receive the special honor of being invited to a death anniversary, you are in for an unforgettable experience. As mentioned before, this isn't a somber day, the atmosphere is full of warmth and cheerful energy. And since this is a uniquely Vietnamese tradition, knowing a few simple "dos and don'ts" will help you navigate the event smoothly and avoid any awkward moments.

The Dos

- Dress respectfully: Think of what you might wear to a nice family brunch. Smart casual attire, such as a collared shirt and trousers for men, or a modest dress or blouse for women, is a perfect choice.

- Bring a small gift: This is a lovely gesture. A basket of fresh fruit or a nice box of tea cakes is common and much appreciated.

- Greet the elders first: It’s a beautiful part of Vietnamese etiquette. A nod and a smile to the oldest members of the family always show great respect.

- Enjoy the feast: Feel free to try the food you’re offered! The compliment, "This is delicious!" ("Món này ngon quá!"), is the best gift you can give to the host who prepared the meal.

The Don'ts

- Wear all black or all white: Traditionally, these are colors for funerals. Opt for neutral or soft colors instead.

- Be loud during the ceremony: The moment the host is lighting incense at the altar is the most sacred. Take a few moments of respectful silence.

- Firmly refuse everything: Your host's hospitality will show in their constant offers of food and drink. If you’re full, a polite and gentle refusal like, "I'm so full, thank you so much," is much better than a simple "No, thanks."

- Light incense on your own: This is a family-led ritual. Wait to be invited by the host. If you don't feel comfortable, it's perfectly fine to politely decline with a smile and a thank you.

Above all, bring a warm smile and an open heart. Your presence is the most cherished gift.

More Than a Ritual, It's the Rhythm of the Heart

From the home altar to the national temples, ancestor worship connects the past and present with love and gratitude.

The next time you see incense smoke drifting down a Vietnamese street, hopefully, you will see more than just a ritual. You will see a story of roots, of connection, and of a culture that cherishes its past to stand firmly in its future.

If this glimpse into Vietnam's spiritual heart has inspired you, there's no better way to experience it than from the back of a vintage Vespa. To truly discover the hidden alleys and authentic stories of Saigon, consider a tour with the team at Vespa A Go Go.

Other tips

- Ho Chi Minh City: A Global Melting Pot of Cultures on a Plate

- Essential Vietnamese Lunar New Year Decorations for Your Home

- Vietnam Symbolism: The Soul, Identity, and Resilience of the S-Shaped Land

- Vietnamese Dragon: Meaning, Legend & Cultural Identity

- Islam in Vietnam: Distinct from the Rest of the World

- Cyclo Vietnam: The Insider Guide to Vietnam’s Most Iconic Pedicab Experience

- Is the Water Puppet Show Worth It? An Honest Review & Deep Dive into Vietnamese Water Puppets History

- Celebrating Mid-Autumn Festival in Vietnam 2025 | The Ho Chi Minh City Insider's Guide

- What's happening on September 2nd in Vietnam? Vespa A Go Go Explains It All!

- Vietnam Independence Day: 80 Years. One Unforgettable Celebration

- Beyond the Sights: An Insider’s Guide to the Soulful Music of Vietnam